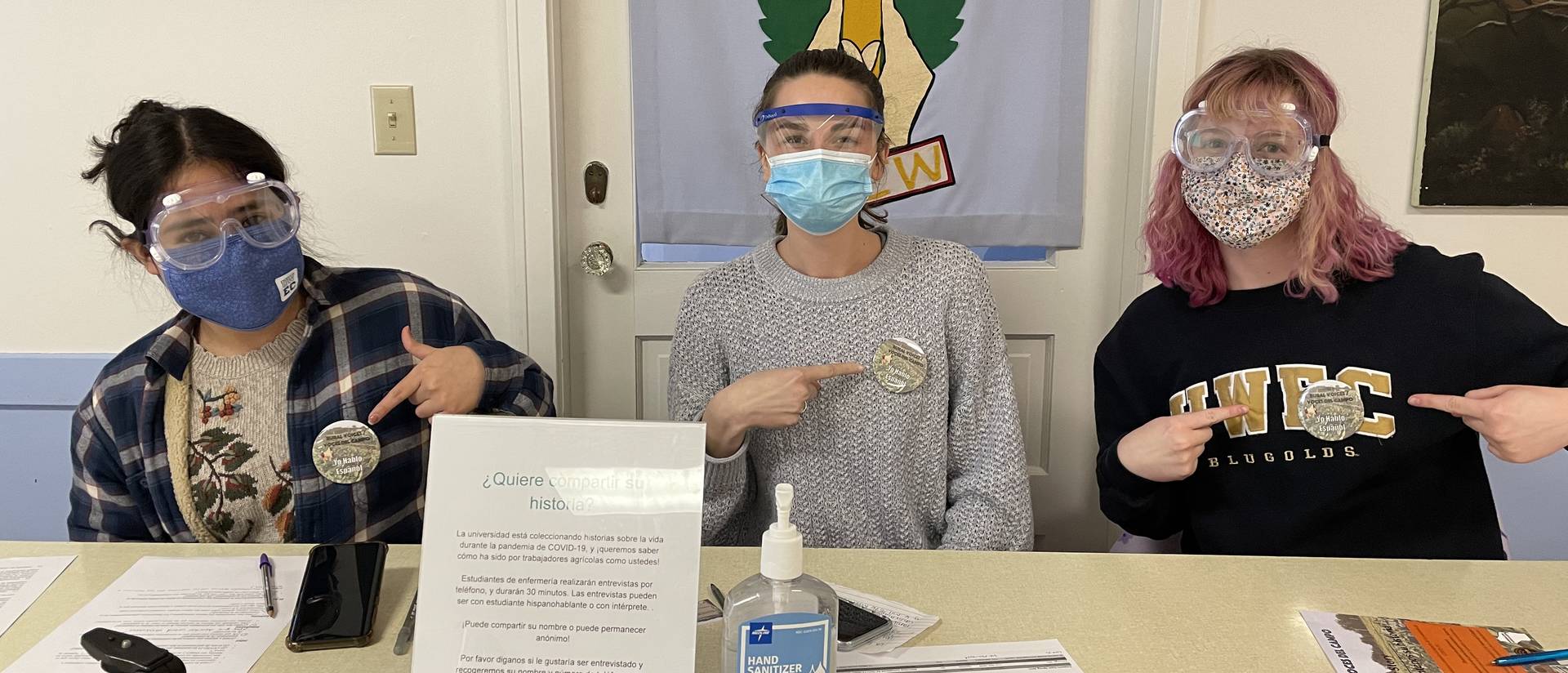

Photo caption: Blugolds (from left) Breida Torres Berumen, Lucy Hobbs and Claire Ganschow are capturing and preserving stories shared by Spanish-speaking populations in western Wisconsin about what life has been like during COVID-19. The multidisciplinary team includes students from public history, nursing and Latin American and Latinx studies. (Submitted photo)

A team of University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire faculty and undergraduate and graduate students who are studying public history, Latin American and Latinx studies, Spanish and nursing are working together to capture stories about what life has been like during COVID-19 for western Wisconsin’s Spanish-speaking populations.

Documenting and preserving their experiences through oral histories will help current and future generations better understand the pandemic and its impact on diverse populations in the region, says Dr. Cheryl Jiménez Frei, an assistant professor of history and Latin American and Latinx studies.

“As historians, archivists and museums document the pandemic in rapid-response collection projects, we must preserve voices from the communities who have borne the brunt of the pandemic, and who often have been silenced in archival collections and official histories,” Jiménez Frei says.

Faculty leading the “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” project are Jiménez Frei; Dr. Elena Casey, assistant professor of languages and Latin American and Latinx studies; Dr. Lisa Schiller, associate professor of nursing and director of nursing graduate programs; and Dr. Lorraine Smith, assistant professor of nursing. Greg Kocken, UW-Eau Claire’s archivist, also is involved in the project.

Giving voice to marginalized communities

“Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” grew out of a broader oral history project that originally centered on the UW-Eau Claire and greater Eau Claire communities.

Last spring, Jiménez Frei’s public history students began capturing stories and artifacts to document the pandemic’s impact on the region. They worked with Kocken and the Chippewa Valley Museum to create the “Chippewa Valley COVID-19 Archive.” They also contributed to “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a COVID-19 archive that began at Arizona State University but now includes partners all over the world.

The archive, which now includes hundreds of collected objects and nearly 100 oral history interviews, evolved during the past year to include stories and artifacts from throughout western Wisconsin. Its new name, “Western Wisconsin COVID-19 Archive Project,” reflects its expanded scope.

“The oral history interviews conducted last spring provide a fascinating comparison to interviews being conducted right now,” Kocken says. “These interviews will provide enduring value; an opportunity for future scholars to understand the pandemic’s impact in our region at different moments in time.”

UW-Eau Claire students (from left) Claire Ganschow, Wendy Villalva and Alexis Polencheck visited farms and other locations to interview Spanish-speaking people about their experiences during the pandemic. (Submitted photo)

While students did an amazing job launching the archive, Jiménez Frei still worried about the voices that often go unrecorded, asking how they could give those voices room to share their stories.

“In my classes, I always remind students the only way we know anything about the past is through the pieces that are left behind,” Jiménez Frei says. “We must put those pieces together to understand the larger story. But what happens if no one wrote down your story? It means your story is not told. It means there is a silence in archival records of certain experiences and histories.”

Too often, Jiménez Frei says, the voices that are missing are those of marginalized groups, including women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community and Indigenous peoples.

“These silences may emerge from the simple fact that no one asked their stories; that those in power did not see them as important,” Jiménez Frei says. “Or they may stem from long histories of discrimination that instill a distrust of institutions. Either way, it illustrates how archives can reproduce structures of power, and that is something I wanted to avoid with this project.”

Kocken agrees, saying stories collected through “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” will make the larger archive an even more meaningful tool for scholars and others trying to understand this time in history.

“Our goal is to erase archival silences by connecting with an audience that is often absent from the archival record,” Kocken says. “Conducting oral history interviews in Spanish is an important expansion of the project and helps us to bring normally silent voices into the archive.”

“Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” is necessary because COVID-19 has hit Black, Latinx and Native American communities the hardest, exposing myriad racial disparities in social, economic and health care systems in the U.S., Jiménez Frei says.

Migrant and undocumented farmworkers — essential to Wisconsin’s dairy industry — are especially vulnerable, Jiménez Frei says. They face increased COVID-19 risks due to factors such as crowded housing and working conditions, and obstacles to seeking medical care, including a lack of insurance, sick time and transportation, income insecurity, language barriers and fear due to their legal status.

“In working on COVID-19 archives with my students, I could not shake the question: Who will record these important stories?” Jiménez Frei says. “I want to record the experiences of these essential workers, drivers of the state’s economy, not just for posterity, but hopefully to help create policy in the future that can mitigate some of the hardships these communities of essential workers face.”

The perspectives these community members share through their interviews also are important to current health care workers, policymakers and residents looking to improve the health and well-being of rural communities in and beyond pandemic contexts, Casey says of the project’s value.

“Listening to community members’ perspectives of the pandemic and how it impacts them is essential to the crafting of successful health outreach, education and services,” Casey says.

An interdisciplinary approach

Jiménez Frei and Casey, both affiliates with UW-Eau Claire’s Latin American and Latinx studies program, planned to work with students from public history, Spanish and Latin American and Latinx studies to record and preserve the farmworkers’ experiences.

Nursing students helped public history and Latin American and Latinx studies students connect with Spanish-speaking farmworkers they know through their clinical work. (Submitted photo)

However, they quickly realized that reaching the farmworkers they most wanted their students to interview was a problem. Both Casey and Jiménez Frei joined UW-Eau Claire’s faculty shortly before the pandemic, so they had not yet built relationships with the farming communities in western Wisconsin.

They knew that nursing faculty and students had been working with farmers and immigrant communities for years through their Rural Immersion Clinicals program. They invited nursing into the project, knowing they already are trusted by many farmers and farmworkers.

“We’ve not had time before the pandemic to build the relationships necessary for dairy community members to trust us and our students with their stories,” Casey says. “In partnering with us, nursing allowed us to work with the community partnerships they have built over the last decade.”

With their expanded team — and funding from the Albert Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest at Villanova University and UW-Eau Claire’s Office of Research and Sponsored Programs — in fall 2020, they began documenting and archiving oral histories of Latinx farmworkers.

The multidisciplinary approach was even more valuable than they expected, with everyone from farmworkers to students benefiting from the collaborative approach, Casey says.

“Our Spanish-speaking students are helping at the nursing clinicals when they need an extra interpreter or a document translated quickly, and the interviews that the Spanish, LAS and history students are collecting will be used to inform the services provided in future nursing clinicals,” Casey says.

The multidisciplinary nature of the project was such a positive experience for students that faculty already are talking about future projects that will allow students to partner and collaborate across disciplines.

“It really underscored for students how work in the sciences and the humanities intersect, and in so many ways depend on each other to benefit society as whole,” Jiménez Frei says . “We need research and advancements in the sciences, but we also need these things in the humanities, and more often than some may think, these imperatives overlap. Collaborations like this really showed the students how working across disciplines is incredibly rewarding and is a benefit to us all.

“It gave the students in history, Spanish and nursing a strong respect and deeper understanding for the work of their peers in different disciplines, and ways that they can collaborate further in the future.”

Jiménez Frei trains team members across disciplines in oral history best practices and mentors the history interns who curate interviews for the digital archives.

Casey trains interns to recruit and perform oral history interviews in Spanish; helps review and revise the Spanish-language communications and medical documents, interview questions and transcriptions that students create; and provides them with the specialized vocabulary necessary to interpret in the medical contexts. Nursing faculty coordinate the vaccination clinics and other health care-related aspects of the project, allowing team members time to interview farmers and farmworkers.

“Without the collaborations, the project could not have worked,” Jiménez Frei says. “Every partner played a role in making the whole thing come together. Without the connections and trust the nursing program had already established with farm owners and workers, the students would have struggled to gain access to these communities to document their experiences in an open and authentic way.

“Without the language skills of the Spanish and Latin American and Latinx studies students, the workers could not have shared their experiences in their native language. And without the training and work of the public history students, these oral histories could not have been properly conducted and archived for future generations.”

A valuable learning experience for students

All students in the project are gaining valuable experience in public health, rapid-response collection efforts, digital archives and curation, conducting oral histories, Spanish conversation and translation, and understanding and addressing archival silences, Jiménez Frei says.

“Speaking for the Spanish-language interview component of the project, the students are the heart of what we do,” Casey says. “They go to clinics to perform interviews, field follow-up calls and virtual conversations with dairy farm workers, make new community contacts, test recording and transcription technologies, and create Spanish- and English-language transcriptions so the experiences shared by our agricultural communities may be accessible to the broader public in Wisconsin and the nation. All the while, they look for ways to use their linguistic and cultural training and awareness to positively impact the health and well-being of the communities they engage in their interviews.”

Spanish-speaking interns also serve as interpreters at COVID-19 vaccine clinics, provide handouts of community health resources at their interview stations, and help nursing clinicals translate essential medical documents, including vaccine consent forms and questionnaires, into Spanish.

The project allows students to use their liberal arts education to engage their local community in a meaningful way, Casey says.

“I hope the students take with them an awareness of how crucial their linguistic and cultural competencies are to promoting healthy and inclusive communities here in the Midwest, as well as an awareness of the variety of ways that they can use these abilities in their future careers,” Casey says. “As interns, students perform tasks related to a variety of disciplines, including journalism, public history, medical translation and interpretation, graphic design, the digital humanities and public health.”

Casey, who teaches “Spanish for Health Professions,” says the “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” project is an extraordinary learning opportunity for her students.

“I am always looking for ways for students to interact with Latinx communities in health contexts, and I knew those opportunities would be necessarily limited during the pandemic,” Casey says. “So, when Dr. Jiménez Frei approached me about working together, I was immediately on board.”

Students also are gaining substantial experience in service-learning and community work, and they see how their skills can be used in real-world situations that will benefit others, Jiménez Frei says.

“The project took students’ skills beyond the university to work with vulnerable and underserved populations, helping them to better understand the communities around them, and the contributions and struggles of migrant and undocumented workers,” Jiménez Frei says.

The core team of students on the project included three public history interns, four Spanish and Latin American and Latinx studies interns, as well as the nursing students who helped them make connections with farmworkers at the site of nursing clinical visits.

Public history interns do a lot of work on the back end of the archive, meaning they help build and organize the archive, curate items coming in and add metadata to interviews and transcripts as they are filed in the archive. Spanish students conduct interviews on site with workers in Spanish, while the public history interns also go to site clinicals to conduct interviews in English, with farm owners, some farmworkers, veterinarians and others who worked on or around the farms.

“The students overall were the most successful getting interviews on site, at clinicals where nursing students were administering COVID-19 vaccines to rural farmworkers,” Jiménez Frei says. “It was a fantastic partnership, and the students all went above and beyond in their ability to collaborate with each other across disciplines.”

As students practiced and honed their interview skills, they edited the standard questions as needed, the Spanish students under the direction of Casey and the public history interns working with Jiménez Frei. Public history interns also worked with Jiménez Frei and Kocken to process and preserve interviews and transcripts for the archive.

“We could not do this project without our students,” Jiménez Frei says. “Their curiosity, collaboration, ability to think on their feet and willingness to take on new challenges are all worthy of recognition. I could not be prouder of all the work they have done on the project.”

Jiménez Frei hopes these students now better understand the diversity of the rural Midwest, the role of Latinx workers in economic and agricultural systems in the U.S., the lives and struggles of undocumented workers and the intersections of race, power and structural inequality in the U.S.

Students should also take with them a better understanding of the power of oral histories to capture everyday voices and perspectives, and how these voices and perspectives are incredibly valuable to preserve, Jiménez Frei says.

“For my public history students — who one day are likely to work in museums or archives — it is my hope the work they have done will make them think deeper about archival silences, and that this is something they take with them into their professional lives,” Jiménez Frei says. “The project better prepared them to be attentive to issues of archival silences and how to address them, and overall to see the power of archives to uplift marginalized voices.”

Making the most of the opportunity

The students say they have taken all of those things and more from the archive project.

Alexis Polencheck, a junior history major with a public history emphasis, has visited farms and vaccination clinics to complete interviews and has worked on the project’s archive to reformat, place and process new items, and make the website more accessible to the public.

“I really appreciate that the oral history project’s focus is on rural voices since I do come from a small town and their voices are just as important as urban,” says Polencheck, who is from Ashland. “I took Dr. Jimenez Frei’s public history course last fall where we learned the basics of oral history interviews and the processing involved, so I had worked on the project already and was excited to go deeper into it.”

Thanks to the oral history project, she is increasingly comfortable approaching strangers to ask for their personal stories, a valuable skill for someone interested in public history, says Polencheck, who also is pursuing a minor is art history and a certificate is English critical studies in literature, culture and film.

“All the skills I’m gaining will be helpful in the future,” Polencheck says. “I know how to work on an online archive, I can conduct oral history interviews and I can process different types of items. I hope to work in a museum in the future, so this experience is helping me grow in many different fields that will come into play. I hope to work on the backside of museums, so the archive work is a great start.”

Polencheck worked on the project with two other public history interns, Emily Martinsen and Morgan Moe, both public history graduate students who hope to work in museums in the future.

Claire Ganschow, a Latin American and Latinx studies major from La Crosse, says being part of the project has made her realize how important migrant workers are to communities, urban and rural, in Wisconsin.

“Hearing their stories and understanding more about their lives is a way to give back for all the work they do in our communities because they really are the backbone of Wisconsin’s economy,” Ganschow says. “Their stories are important and deserve to be heard and shared.”

Breida Torres Berumen, a junior pre-physician assistant student with a major in biology and a minor in Spanish for health professions, says the people she interviewed were eager to share their stories.

“People do want to tell their stories,” says Torres, who grew up in Mexico before moving with her family to Maiden Rock when she was in high school. “I think they are hesitant only because no one has ever asked them to share them before.”

Wendy Villalva agrees, adding that the stories people are sharing are fascinating.

“Everyone’s story is unique,” says Villalva, a biology major from Brodhead. “It is a privilege as an interviewer to have insight into another person’s life and it is always so intriguing to learn what other human beings have experienced and what their takeaway from their experience is.”

Among the lessons taken from the project is the importance of being nimble, says Lucy Hobbs, a nursing and Spanish major from Somerset.

“We have learned to be adaptable with the project and to initiate trusting relationships with the farmworkers,” Hobbs says. “I have learned from this project to never assume anything about an individual or their story. I haven’t ceased to be surprised at aspects of every single interview and continue to learn more from each person I talk to.”

Next steps

While farmworkers remain a focus, “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” has expanded to now include all Spanish-speakers in the region.

“We have undergone a growth spurt since beginning the project and are now broadly interviewing rural communities in our region, in addition to farmworkers,” Casey says. “By intentionally seeking out voices that tend to be marginalized — due to factors like language, distance from urban centers and ethnicity — we are making our archives more representative of the diverse communities in the rural Midwest.”

Jiménez-Frei and Casey have been awarded a Summer Internship Program grant from the Albert Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest at Villanova University, in partnership with “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a global COVID-19 archive created by Arizona State University. A UW-Eau Claire student-faculty research grant also provides some funding for the “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo" project.

They will use the grant monies to hire a graduate student from Villanova to continue work on the project this summer, assisting Jiménez-Frei and Casey with Spanish-language interviews, transcription and translation, and digital archive development and curation.

New interviews and artifacts also will continue to be added to the “Western Wisconsin COVID-19 Archive” project, Kocken says.

The oral histories already collected through both projects are available on the “Western Wisconsin COVID-19 Archive” and the global “COVID-19 Archive: A Journal of the Plague Year.”

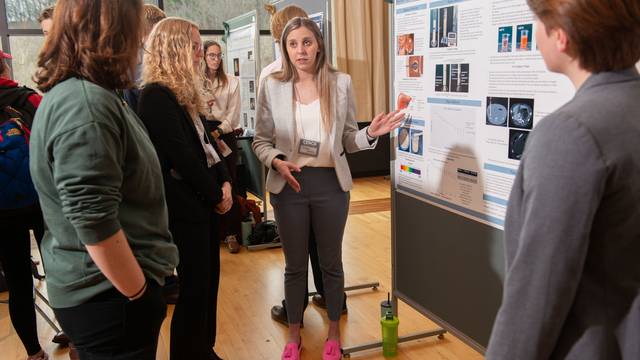

Faculty, staff and students involved in both the “Rural Voices/Voces del Campo” project and “Western Wisconsin COVID-19 Archive Project” are sharing their work at professional conferences and meetings. The students involved in the project also presented their work this spring at the 2021 Provost’s Honor’s Symposium.